In his classic story of spies and crossed fates, “The Garden of Forking Paths,” Jorge Luis Borges imagines a labyrinthine manuscript, “a growing, dizzying web of divergent, convergent, and parallel times.” The fictional book of the story is unfinished, not only because its author is murdered before he can complete it, but also because its form is necessarily infinite, encompassing all timelines generated by every decision of every character: an inescapable maze.

Yet the structures of some real books resemble what Borges had in mind. Not only do these novels challenge our understanding of narrative linearity, they invite us to participate in the making of the story, to play along with each reading. And just as with a well-built maze, getting lost in each of these books can be a lot of fun.

Milorad Pavić, The Dictionary of the Khazars

Deserving of consideration as a classic of 20th century fantasy, this novel features a mysterious sect of dream hunters, games with time and mirrors, and a language preserved by birds. Something like an analog Wikipedia entry—though published a year before the invention of the Web—the book is actually three fictional dictionaries, each containing a different perspective on a playfully mythologized version of the Khazars, a semi-nomadic people who once occupied land between the Caspian Sea and the Black Sea. The narrative threads span continents, centuries, and dreams; to follow them is to play at being both a folklorist and a treasure hunter.

Italo Calvino, The Castle of Crossed Destinies

When asked to write a brief booklet to accompany the reproduction of a fifteenth century deck of cards, the Italian author “was tempted by the diabolical idea of conjuring up all the stories that could be contained in a tarot deck.” The result is this novel, which he wrote by laying out all the cards in a grid and then reading them from top to bottom, side to side. The narrators of the resulting linked stories—mute from some unknown trauma—tell their tales of love, loss, and adventure using cards rather than words.

Lily Hoang, Changing

Published by the reliably excellent Fairy Tale Review Press, this novel is modeled after the I Ching, the ancient Chinese divination system. At the back of the book, the author includes cut-outs of a paper cup and numbered tiles, which readers may use to select chapters at random; the chapters are shaped like the hexagrams of the I Ching. Weaving together nursery rhymes, oracular statements, and a coming-of-age tale, Hoang fuses storytelling and fortunetelling to original, often devastating effect.

B.S. Johnson, The Unfortunates

This book comes in the form of twenty-seven separately bound sections, packed together in a single box. One section is labeled “FIRST,” another is “LAST,” and the rest are meant to be shuffled. The largely autobiographical story is about a man contemplating the death of a beloved friend while on a sportswriting assignment. What’s remarkable about the book is how its shuffled structure mirrors the rambling, leaping movements of the human mind, “the circuit-breakers falling at hazard, tripped equally by association and non-association, repetition….”

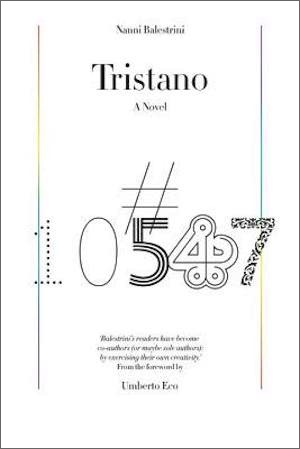

Nanni Balestrini, Tristano

Another shuffleable novel, but this one you don’t have to shuffle, because every copy of the book has been printed with the pages in a different order (I’m the proud owner of version #11476). A love story—and a reimagining of the Tristan and Isolde legend—the novel blurs the identities of the main characters (both referred to as “you” and “I”and sometimes “C”) along with geographical place names (also often “C”) to the point where the story gathers itself up into a dreamlike whirl of cigarettes, taxis, telephone calls, and frustrated revolution. “A book is endless books and each of them is a slightly different version of you.” So reads an emblematic line on page 8 of my copy, but in yours it will probably be someplace else.

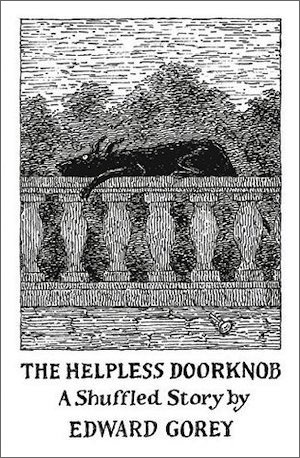

Edward Gorey, “The Helpless Doorknob: A Shuffled Story”

Now to cheat a bit. First, this is entry #6. Second, this is technically a story, not a book. Third, I only just found out about “The Helpless Doorknob,” and I’ve never held a copy in my hands. I’ve seen it online, though, so I know that each entry in this deck of twenty cards features someone whose name starts with A, most of whom are doing something terrible or at least something terribly suspicious. In any case, I can’t leave Edward Gorey off this list, because so many of his little books are labyrinths without solutions. Fellow admirers of his work will likely think of The Awdrey-Gore Legacy, which is a classic murder mystery broken down into its constituent parts, or The Fantod Pack, a fortunetelling deck which may reward its readers with “mumbling sickness,” “a secret enemy,” or “an accident in a stadium.” Each may be read dozens of different ways, but I recommend a hundred or more visitations.

Originally published February 2015

Jedediah Berry is the author of the Crawford Fantasy Award-winning novel, The Manual of Detection. His story in cards, “The Family Arcana,” was published as a poker deck by Ninepin Press, and was a finalist for a World Fantasy Award. His other works of short fiction appear online at Tor.com and Interfictions; in the journals Conjunctions, Unstuck, Massachusetts Review, Chicago Review, and Fairy Tale Review, among others; and in anthologies including Best American Fantasy, Year’s Best Science Fiction & Fantasy, Best Bizarro Fiction of the Decade, Salon Fantastique, and Cape Cod Noir.